Parenting with a Disability: Jordan's Story

The Pregnancy and Parenting Support project exists to assess and raise awareness of the support needs of people with disabilities who are or want to become parents. To further that mission, we are amplifying the voices of parents with disabilities to share their experiences.

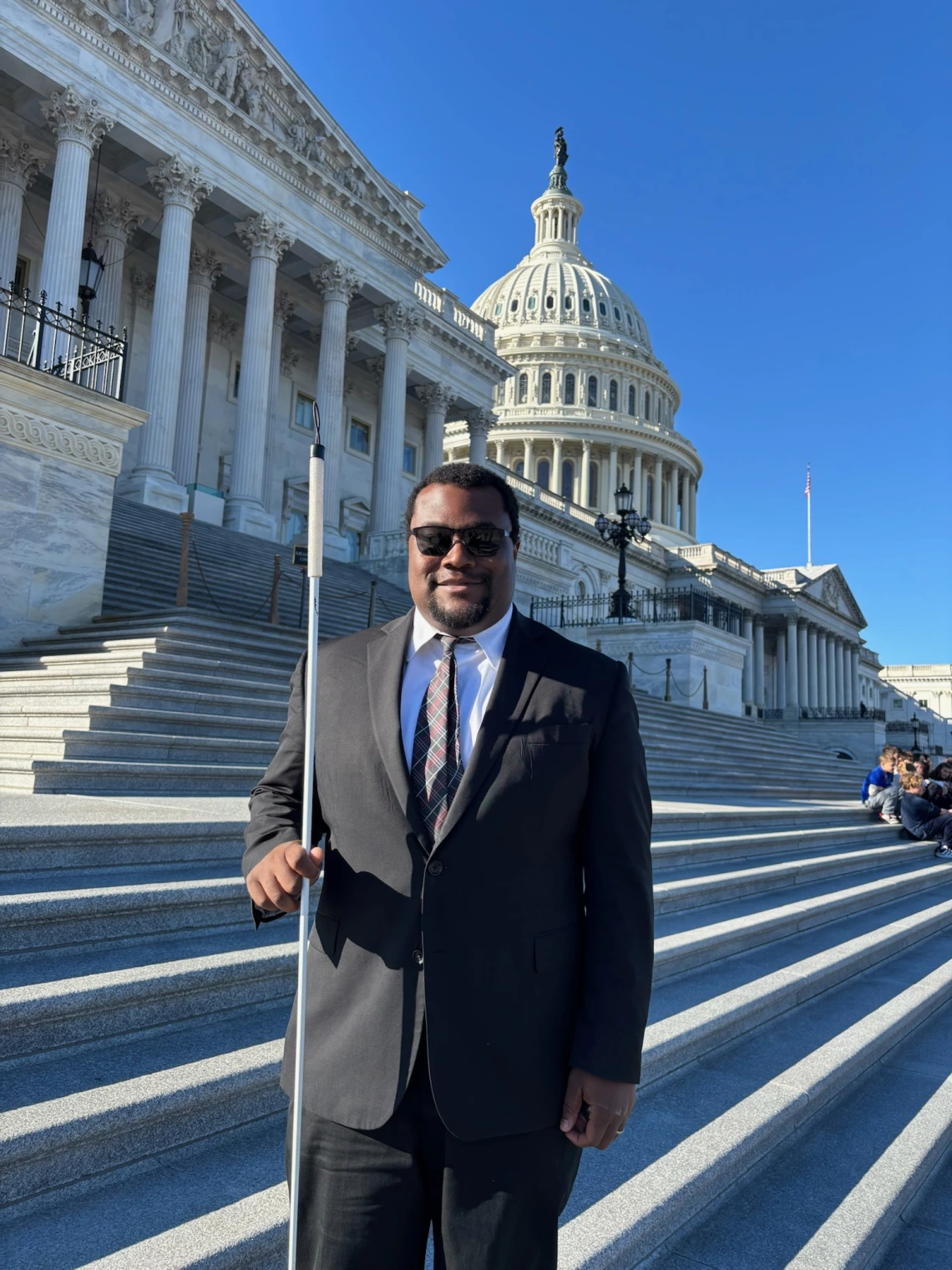

Meet Jordan Moon.

He is the father of two children, and the director of Phoenix Center of SAAVI Services for the Blind. He was born with Peter’s Anomaly, which led him to progressively lose his vision. The Sonoran Center’s Content Coordinator, Drew Milne, had the opportunity to sit down with Jordan and discuss the progress that has been made for disabled parents, areas where there is more work to be done, and the magic of fatherhood that’s there through it all.

Drew: Introduce yourself and talk about your parenting journey

Jordan: My name is Jordan Moon. I am the director of the Phoenix Center of SAAVI Services for the Blind as well as Vice President of the National Federation of the Blind for Arizona. I also sit on the Phoenix MERS commission for disability issues. I have a wife who is blind as well and we have two kids; a six year old daughter who is an incredible musician, she plays the piano well, she’s really smart, and she is blind. She reads braille and travels with a cane. I also have a one-year old son who is just now learning how to walk and is definitely a handful! But an awesome handful. He’s great. My journey as a blind parent, and with my wife, has been interesting. I would say the most important thing is to not be afraid to connect with resources, but also to have a positive philosophy. In my case in particular, a positive philosophy of blindness, which says, essentially, that it’s okay that you’re blind and you have a disability, but we are not going to use that as an excuse. We as parents extended that philosophy from our personal lives to our kids. I was telling somebody recently that the best thing about being a parent is when you’re just at home with your family and everything feels normal - there’s nobody you have to impress, it’s just you, your kids, and your wife - that’s when I’m in my happy place. So that’s been our journey there.

Drew: Tell me more about your disability and what it means to you.

I was born with a condition called Peter’s Anomaly. Growing up, I did everything in my ability to make it look like I was not less-than. So I faked it a lot, but I did have some vision.

Peter’s Anomaly is a condition where your cornea is clouded. I tell people, when they get out of the shower and you look in the mirror and it’s all steamy, that’s what it looks like out of my vision. With Peter’s Anomaly, I was able to see somewhat, but only during the day. So, I would fake it, but my mom and dad were smart enough to have me learn braille at a very young age. I learned braille very young, and I was able to use that throughout school even though I had vision. I was playing both sides of the field, you could say, because I had friends at a local nonprofit that were blind, so I hung out with them on the weekends, but all my friends at school were sighted. It was really kind of hard to do mentally, but it helped me today to relate to a lot of people and be open about it. I think that for me, it wasn’t until college, in maybe 2010, that I started losing more vision and I had to start using the cane more often. That was a blessing to be honest, because I needed that push to the other side, you could say, to force me to rely on my braille skills and use a screen reader. Now, I have no choice but to embrace it. It has helped me accept myself more and be proud of saying the word “blind”. That was always hard to do, especially around family. I’m content with where I’m at, and I’m grateful for that journey, because it allowed me to connect with many people going through similar situations or who have lost their sight quickly. I can tell them “I know it’s a switch-up, but you may like this journey looking back, because it helps you embrace who you truly are.”

Drew: Tell me more about being a father with disabilities.

Jordan: I was talking to my friend about this. My friend is blind. He’ll be a blind father. What I was telling him is it’s interesting as a father because when it comes to say, breastfeeding, you can’t do that, so what are you going to do to show your role and help out? Change a diaper? I see my role as: He’s crying for a while? Let me take him outside. There are ways we can help out.

As a disabled father, we have an awesome role to play in being able to support your partner, disabled or not. That’s your role. You have to support your significant other, and most importantly you have to show your kids you can play that father role and be there for them. I have another friend in a wheelchair. His wife is not disabled but he is. I saw him at a conference, and his kids ran up to him, “Daddy!” and jumped on his lap in the wheelchair. I thought, “That's wonderful. You can tell that’s genuine love.” That’s what it’s about. Don’t let your judgement be clouded. When your wife is in labor, you can be there in the hospital - roll over to the bedside and hold her hand. Go in there and tell the doctors “Can I help out? I got this”. Be an active participant. Don’t sit back as a father and let things pass you by, because it’s your kid too.

Drew: What are some things that have been helpful for you in your parenting journey?

Jordan: There are resources that I think every blind parent, or parent with disabilities, needs to connect with. They need to be able to connect with local and national resources that can support you in legal matters, advocacy, or even practical things. Some of the resources that

I lean on which have really helped me are the National Federation of the Blind. They have a whole page dedicated to a blind parents mentoring program, and there are a lot of resources about blind parenting available through the National Federation of the Blind. Locally, the National Federation of the Blind of Arizona as well as the Governor's Council on Blindness and Visual Impairment have really tried to do a lot with educating blind parents on small things - how to change a diaper, all the way to how to connect with a teacher if your kid needs homework help when you’re blind and your kid is sighted, how to deal with that situation.

I think one of the most important things too is to understand that legally, your rights as a parent are protected in AZ. We, through the National Federation of the Blind, have passed a law that deals with basically making it illegal to take your kid away from you solely based on your blindness. Of course, if you’re blind and you aren’t a good parent, that still applies, but for it to be solely based on blindness, now that’s illegal. You can have the freedom to know that you’re protected and it gives you more confidence as a parent.

Drew: What are some things that you’ve found difficult about pregnancy and parenting?

Jordan: I’ll talk a bit about the helpful things about pregnancy. When dealing with the situation, I think one of the most nerve-wracking things for people with disabilities is, “How are the doctors and nurses going to interact with us?” As far as paperwork goes, luckily things are now digital, so where my wife went, all the material she needed to learn was all accessible. That was a really good thing. But the perception - that was the most nerve-wracking part.

There were differences, too. The first time we were pregnant, we were very nervous, and I think that came off to the staff at the hospital we were at, and even in different classes we were attending. They would ask questions like “Are you guys going to be okay? Do you need me to show you how to do this? Make sure you’re holding her like this-” They’d be overly helpful, I would say. Not because they were trying to be mean, we were just very nervous. But on the second go-around, my wife and I (and it could have been because we had a kid already) were very confident. We were just like “We know how to do this”. I felt like, the more confident you are, the less overbearing people will be. They’ll be like “Oh, clearly they know what they’re doing.”

It was kind of interesting; when my son was born, we had parents who were deaf right next door to us. The same doctor was treating both of us. She was like, “This is quite the day!” I think some of the challenges of being pregnant outside of the general challenges were also dealing with family and making sure that they were confident in us and our abilities. Not like they weren’t, but you’d sometimes hear these (same) questions. But I think it's parallel to the nurses and the doctors, if you present yourself confidently, you’re going to be good.

As far as parenting, one of the challenges I would say, generally speaking, is the need to always prove yourself. I feel this intense stare that I get when I’m dragging my son from behind in the stroller instead of pushing him because I have to use my cane, or I’m taking a picture with my phone of a piece of paper so I can actually read instructions. They’re not normal things that people see. So, I’m like “if I’m going to do it, I have to do it the right way.” Now, I try to not always care about the pressure, but it’s hard to not understand that it’s there. That’s kind of the need to prove yourself when you’re out and about.

Another challenge, I would say, is when my son is going to be older. Because he can see, I know there are going to be people who will say, “Oh, you’re helping out your mom and dad, good for you, son,” because I’ve seen it happen with friends who are blind or have other disabilities as well. I was in a panel and somebody was mentioning how the doctor, when she was there to look for her daughter, because her daughter was 19 and she could hear, her daughter ended up interpreting for her mom, and the mom was insulted because the daughter was there because she was sick. What happened eventually was, because the hospital couldn’t provide an interpreter, they told the mom “well since she’s 19, she technically doesn’t need you” and they kicked her out. You see these things happen all the time in the disability community and I think those are some of the challenges: to overcome the misperceptions, the stereotypes, the inaccessibility, and that pressure that seems to be placed on us as disabled parents to be able to perform.

Drew: How do you navigate stigma and stereotypes?

Jordan: Sometimes you can’t, right? I wear sunglasses as a blind man, because it protects my eyes from the sun, even inside. I’m very sensitive to light. So, sometimes you can’t avoid a stereotype, but what you can always do is put your best foot forward. The way I overcome it is knowing that it’s okay to fail. Every parent deals with this - I don’t know one brand new parent who isn’t nervous about changing a diaper. Blind, sighted, deaf, whatever. It doesn’t matter. Pregnancy is pregnancy, right? I have a friend who just found out she is pregnant. Fantastic, I’m very happy for her. She’s asking us all types of questions that have nothing to do with blindness - because she’s not blind. Just, “Hey how did you guys do this” or “What doctor did you go to for this?” These are things that let me know we’re doing the right thing.

It doesn’t matter what somebody who barely meets you on the street thinks. What matters at the end of the day is what your kids feel, and their experience, and how they see you dealing with those stereotypes and not being afraid to be yourself. I’m looking forward to meeting that challenge as our kids get older. One of the stereotypes is that we won’t be involved in the PTA for example, or helping out at school, anything like that. That’s nothing further from the truth. We can easily make phone calls, help out with things, and our kids need to see that we’re not going to give in. They need to understand that we are the parents, and they need to have pride in who their parents are, and I’m looking forward to meeting that challenge head-on.

Without community, I think it’s impossible to maintain that positive viewpoint, because it’s few and far between - people you can identify with and connect with. You try to do your best, but it’s impossible to do it alone.

Drew: What has your experience with professionals been like?

Jordan: When it comes to going to doctors offices, or dealing with professionals in general, there is always this nervousness because there are so many unknowns. We now have a very good relationship with our kids’ pediatrician’s office, but that wasn’t always the case. There were a few we took our kids to that focused primarily on blindness. We were like, “there’s more than that.” There was one doctor at the practice we’re at right now who made it very awkward. He’d say things like “You guys are such an inspiration,” every time we came in to see him. Like, we’re not here for us, we’re here for our kids! We now see a different doctor at the same practice, and it’s great when you can build up a rapport and trust. I think people shouldn’t be afraid to move on. I'd say if you can afford it, don’t be afraid to make that change, because your comfort is more important than anything.

I have the same thing dealing with my therapist right now. I had to have a hard conversation with her and say, “I think you’re focusing too much on my blindness. Even though this is something I’m dealing with, this isn’t the main thing I’m struggling with right now.” I had to have that conversation. Sometimes you have to not be afraid to have those tough conversations, and if it’s not working out, don’t be afraid to move on, because you need to get the treatment you deserve.

Luckily now, I have a good rapport with my pediatrician. It may not work out with some but there are some really good doctors and providers out there. There really are, you just need to find the one that works for you.

Drew: What advice would you give to others about advocating for themselves?

Jordan: The number one advice I would say is don’t be afraid. You can practice how you want- talk to someone you can trust like a family member or friend who can work with you on how to approach it. I will say that, unless you’re physically or mentally not capable, a person with disabilities really should try to advocate for themselves. Whether they’re deaf, blind, in a wheelchair, they should try as hard as possible to be the person communicating. I know it’s hard because we don’t always have the opportunity to get interpreters, so there’s a lot that goes into that, but as much as possible you should be the one communicating. That’s hard to do because a lot of times we’ve played that victim role, where we’re so used to people doing things for us or advocating for us - speaking on our behalf. That’s why, to bring it back to the National Federation of the Blind, it’s the National Federation of the Blind, not for the blind, because of and for are very different things. Not everyone, again, has that ability, because maybe their disability limits them in some way, but they can all find a way to have their voice be heard. It has to be their voice, don’t let somebody say “if you want, I can talk to them for you!” It needs to come from you, because that’s where the respect will come from. That’s probably the biggest advice I would give them.

Drew: What are some resources for parents with disabilities that you think there should be more of?

Jordan: I would like to see more summits, conferences, and symposiums; more virtual opportunities for people to connect, and in-person opportunities too. I would like to see a national disabled persons’ right to parent law. I would like to see maybe a general website, with different parenting resources. Like, “Are you a parent with disabilities? Here are some links to resources that could help you”. There isn’t really a centralized place where a parent with disabilities can learn about their rights, like how the ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) protects them. Maybe it could link to some how-to videos on Youtube. Like, “How to change a diaper if you’re in a wheelchair” “How to change a diaper if you’re blind” Things like that would be great.

This is part of my mission, to educate parents with disabilities. I feel like the more we have parents with disabilities out there - a lot of kids they have won’t have disabilities, but they’re going to be able to shape how society feels about people with disabilities. So it’s all connected.

Drew: At the Sonoran Center, we believe that disability is not a deficit, but another way of experiencing the world.

Jordan: That’s part of what makes us human, right? Some of us can walk, some of us can’t, some of us can’t see, others can.

Drew: Final thoughts?

Jordan: It’s not all doom and gloom. Being a parent, first of all, is amazing. It’s a great honor. It’s incredible to see the time and effort you put in pay off. When you’re going through life and people are giving you crap and you’re feeling less than, it’s a beautiful thing to know your kids don’t care and they truly love you. When I come home, and my daughter runs up to me, and I hear the bells we put on my son’s shirt so we can track him when he’s walking, I hear them running and I think, “that’s awesome,” after a long day of coworker stuff and so on. If you’re thinking of going down this route, to be a parent, there are challenges, barriers that you’re going to face, from low expectations, things not being accessible, stereotypes, all the things we talked about. But if you really want it, you can do it. Don’t be afraid to reach out, because it’s so worth the journey. Being a parent is the greatest honor of our lives. I truly believe that to raise a kid, to be responsible for the next generation is an incredible, incredible honor, and everyone has the right to that honor, so that’s what I would say to that.